How Chicago Rose from the Ashes with Fire Resistant Steel Buildings

Today steel buildings and skyscrapers define the silhouettes of great cities.

However, in the 1870s, no one even dreamed of massive, multi-story monoliths soaring toward the clouds.

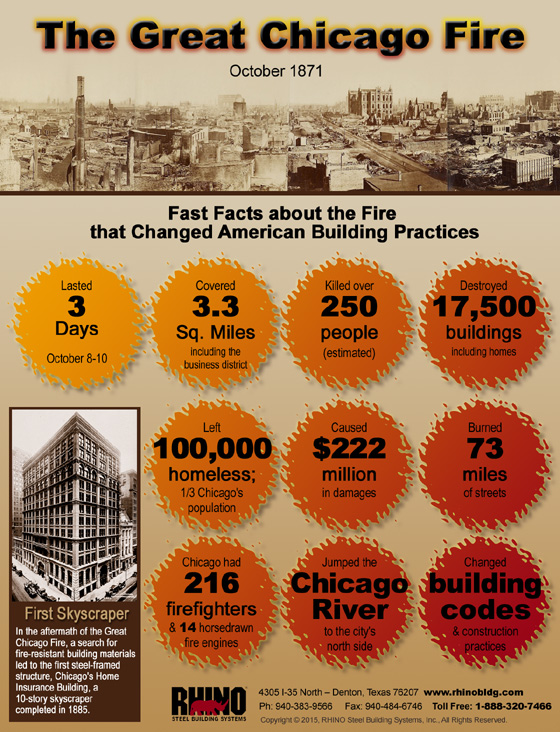

The devastation of the Great Chicago Fire changed commercial construction practices forever, leading to the use of fire resistant building materials like steel buildings.

150th Anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire

On Sunday, October 8, 1871, a fire began in or near the barn owned by Patrick and Catherine O’Leary. Contrary to popular myths about the O’Leary’s cow kicking over a lantern, no one knows the actual cause of the fire.

On Sunday, October 8, 1871, a fire began in or near the barn owned by Patrick and Catherine O’Leary. Contrary to popular myths about the O’Leary’s cow kicking over a lantern, no one knows the actual cause of the fire.

In 1893, Michael Ahern, the reporter who originated the legend of the O’ Leary’s cow, admitted he fabricated the tale.

Whatever the initial cause of the blaze, the results were shattering.

Conditions converged to create the perfect firestorm:

- A 14-week drought with unusually hot temperatures left everything dry and ripe for a fire.

- Most of Chicago consisted of wood-framed structures. Lumber was plentiful and cheap. Even the sidewalks and streets were made of wood.

- Zoning was non-existent. Factories, lumber mills, stores, and houses crowded together in the same blocks.

- The Chicago Fire Department was woefully inadequate for the task. Chicago’s population neared 300,000, yet only 216 firefighters served the city. Three of their 17 horse-drawn fire engines were unavailable during the Great Fire. To make matters worse, miscommunications resulted in a deadly delay getting firefighters to the real source of the fire.

- A strong wind from the southwest drove embers deep into the city. The conflagration burned so hot it created fire whirls— tornado-like vortexes scattering sparks and burning debris high into the air. Witnesses reported seeing sparks and ash everywhere, falling like snow.

People fled in panic, grabbing only what possessions they could carry. Rich and poor alike lost everything in the fire, yet those who escaped at all were blessed to survive.

The Great Chicago Fire Burns Unrestrained

Horace White, the editor-in-chief of the Chicago Tribune, wrote an eyewitness account four days after the fire. In it, he said:

Horace White, the editor-in-chief of the Chicago Tribune, wrote an eyewitness account four days after the fire. In it, he said:

“Billows of fire were rolling over the business palaces of the city and swallowing up their contents. Walls were falling so fast that the quaking of the ground under our feet was scarcely noticed, so continuous was the reverberation. Sober men and women were hurrying through the streets from the burning quarter, some with bundles of clothes on their shoulders, others dragging trunks along the sidewalks by means of strings and ropes fastened to the handles, children trudging by their sides or borne in their arms. Now and then, a sick man or woman would be observed, half concealed in a mattress doubled up and borne by two men. Droves of horses were in the streets, moving by some sort of guidance to a place of safety. Vehicles of all descriptions were hurrying to and fro, some laden with trunks and bundles, others seeking similar loads and immediately finding them, the drivers making more money in one hour than they were used to seeing in a week or a month. Everybody in this quarter was hurrying toward the lake shore.”

City officials expected the Chicago River to create a firebreak. However, the fire leaped across the river, spreading the devastation.

Shortly after crossing the river, Chicago’s waterworks ignited, burning to the ground. Water mains dried up. The fire burned unrestrained.

Rain began late in the evening of October 9. Early in the morning of October 10, the inferno finally sizzled to a halt.

In the Aftermath of the Blaze

Searching the smoldering debris, officials found 120 bodies. However, estimates put the actual death toll higher at 250 or more.

The fire consumed thousands of structures. The Palmer House hotel, opened only 13 days before the Great Chicago Fire, was just one of the thousands of buildings destroyed.

One-third of the population was homeless. Many lost both home and business. As happens in all catastrophes, the poor bore the greatest hardships.

Fire Resistant Steel Buildings Rise Out of the Ashes

Resilient and determined, residents of the Windy City began rebuilding immediately. Within days of the fire, street side business opened in hastily erected sheds and shacks. The poor constructed crude shelters and homes with whatever lumber was available.

Resilient and determined, residents of the Windy City began rebuilding immediately. Within days of the fire, street side business opened in hastily erected sheds and shacks. The poor constructed crude shelters and homes with whatever lumber was available.

Donations of goods, lumber, and cash arrived from across the country and around the world. The Chicago Aid Society distributed donations to the desperate citizens of the scorched city.

In November, just a month after the fire, Chicagoans elected Joseph Madill, co-owner of the Chicago Tribune, as the new mayor. Madill campaigned with promises to institute stringent building and fire codes.

In 1872, the Chicago City Council directed that all new construction must employ fire resistant building materials.

The poor protested the new construction codes, as many wood-framed houses had been completed. Eventually, the city “grandfathered” those wood buildings already constructed.

A second fire engulfed Chicago in 1874, destroyed 60 acres and another 800 buildings.

Insurance companies, battered by the millions spent for the Great Chicago Fire, balked. They demanded steps be taken to force the use of construction fire resistant building materials in construction.

Efforts to Fireproof the City

When it appeared the Palmer House hotel would perish in the fire, John M. Van Osdel, the building’s architect, buried the blueprints for the hotel in the basement. Covered with a thick layer of sand and clay, Van Osdel’s blueprints survived the fire.

Van Osdel became convinced that terra cotta, made from sand and clay, would prove a more fire-resistant building material than wood. When rebuilt, terra cotta tiles covered the roof of the new Palmer House. Framed with iron and covered in brick, promoters billed the Palmer House as “The World’s Only Fire Proof Hotel.”

Meanwhile, the iron industry developed fire-resistant iron through a process that added terra cotta.

The World’s First Skyscraper

Unarguably, the greatest advancement in construction materials was the invention of steel. Without the advent of steel, the birth of the skyscraper would have been impossible.

William Le Baron Jenney, an engineer, designed the first skyscraper using fire resistant steel framing. Steel was lighter and stronger than iron, so it was ideal for multi-story construction.

Using iron and steel to create a cage-like, weight-bearing skeleton, Jenney fashioned the Home Insurance Building in Chicago. Construction on the revolutionary building began in 1884.

The strength of the steel allowed the extensive use of large glass windows on all sides for a much brighter interior. Brick and terra cotta partitions separated the offices.

Ten stories tall and 138’ in height, the Home Insurance Building was an architectural marvel.

Thrilled with the success of the system, Home Insurance added two more floors in 1890, bringing the now 12-story structure up to an astounding 180’ in height.

RHINO Prefab Steel Buildings

Advances in steel technology continue. Today’s steel is stronger— and more affordable and versatile— than ever before.

Doesn’t your next building project deserve the fire resistant building benefits enjoyed by the world’s towering commercial skyscrapers?

Call RHINO Steel Building Systems now to learn how our steel fire resistant buildings— framed with pre-engineered commercial grade steel— bring many advantages to your building projects.

Our number is 940.383.9566.

(Updated 10-6-2021. Originally published 10-6-2015.)